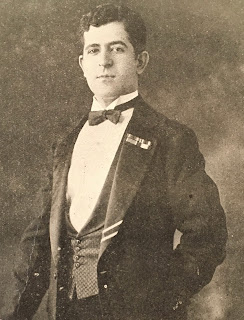

Leon S. Nahmee: The Forgotten Story of a Syrian American Composer and his Adventures in the Ottoman Army, Arab Allied Army, and US Automatic Music Industry

Leon S. Nahmee: The Forgotten Story of a Syrian American Composer and his Adventures in the Ottoman Army, Arab Allied Army, and US Automatic Music Industry

Before the 1930s Arab America could boast of only a handful of musical composers. We have discussed the Maloof Phonograph Company and Alexander Maloof's records, sheet music, and piano rolls in another blog post. This month we relay the story of a lesser-known Syrian American composer, band conductor, and musician whose career peaked in the 1920s and 1930s - Leon S. Nahmee.

Leon Nahmee scored plays, composed and published sheet music, and led military bands although he was not nearly as well-known as Alexander Maloof or Anis Fuleihan. He tried his hand at one of the other popular forms of music technology outside of the phonograph – piano rolls for the self-playing piano or the Pianola. In fact, in the first decade of the twentieth century some argued Pianola's possessed better sound quality than the gramophone. The self-playing piano emerged around the same time as the gramophone cylinder player. Several designs and a prototype for a self-playing organ existed as early as 1876 in Philadelphia as a part of the Centennial International Exhibition (coincidently some of the earliest Palestinian merchants visited the US and one applied for naturalized citizenship according to the work of Linda K. Jacobs), but organs lacked the pneumatic mechanism eventually invented by Edwin Votey that catapulted the self-playing piano into popularity for more wealthy consumers in the early twentieth century. Aeolian (and its Duo-Art brand technology), American Piano Company (Ampico), and QRS were to piano rolls in the United States what Victor, Columbia, and Edison were to flat disc 78 rpm records in the first decades of the twentieth century.

Cylinders became available for home use in the 1890s, and according to A.J. Racy, cylinders and flat discs made their debut shortly after the turn of the century in cities like Cairo. In his article "Record Industry and Egyptian Traditional Music," Racy maintains that musicians visited or relocated to Cairo from Beirut, Aleppo, and Damascus. Companies, like Baidaphon, rose to compete with the European record giants Gramophone Company, Odeon, and the late-arrival to the Middle East - Victor/His Master's Voice. While some argue a self-playing organ could be found in Alexandria, Egypt in the second century B.C., a survey of Arabic language publications from the early 20th century make it difficult to pinpoint when the first modern player piano came into public use in North Africa or the Levant.

Leon Solomon Nahmee was born in Homs, Syria on 19 February 1895 or 1896. Accounts of his early life and musical career were autobiographical. Nahmee demonstrated proficient knowledge of piano playing and composition at an early age and attended the Conservatoire de Paris, presumably for approximately a decade. He completed his course of study and graduated by which time he divided his time between the College de la Sagesse, the School of the Convent of the Savior, the School of the Three Stars, the College of Ahmed Abbas El-Azhary and several other institutions in and around Beirut from 1911-1914.

Although historians mark the beginning of World War I in 1914, the seeds of the conflict might be linked to the first Balkan War as Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria aligned themselves against the Ottoman Empire. After the loss and recapture of Turkish Thrace, the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, and conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, World War I began and eventually Serbia, Russia, France, Great Britain, later Italy, and finally the United States, found themselves at war with Austria-Hungary, Germany, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire. Enticed by Britain and by the idea of full independence from the Ottoman Empire, Arabs within the Empire revolted against the Ottoman Empire (which had recently survived the Young Turk revolt calling for restoration of the Ottoman Constitution). As the Ottomans allied with the Central Powers, the Turkish government commissioned Nahmee to create a military band for its fourth Army Corps. An article by Jonathan Glasser in the International Encyclopedia of the First World War, suggests "Military bands were a ubiquitous fixture for the Ottomans and their allies, as well as for their French and British opponents." To be sure, the entire concept of military bands dates back to thirteenth century Ottoman mehter musicians. Previous to 1909, Ottoman authorities required only Muslims to serve in the military. In 1909, however, authorities passed a law that made military service mandatory for all male Ottoman subjects. Minimum service time varied by branch between two years and four years. In his service to the Ottoman Army, Nahmee’s life is similar to Syrian-American tenor Mohamed ZainEldeen.

Leon Nahmee’s counterpart in the United States would have been African American composer and band leader James Reese Europe. Born in Alabama, raised in Washington, D.C. and New York, Europe rose to prominence as a composer whose Europe’s Society Orchestra performed for and became with renowned dancers Irene and Vernon Castle. James Europe’s Society Orchestra recorded eleven songs on nine discs for the Victor Talking Machine Company. Moreover, Europe as Lieut. Jim Europe’s U.S. Infantry “Hellfighters” Band, James Europe recorded twenty-four songs on the Pathé Phonograph label. Whether Leon S. Nahmee recorded with his Army Corps band or not remains unknown. He certainly could have recorded on Baidaphon or His Master's Voice or the Gramophone label during the 1910s in France, Germany, or even Beirut.

Three years into World War I, and one year after the Sykes-Picot Agreement determining the future partition of the Ottoman Empire, Leon Nahmee joined the Arab Revolt’s Northern Army against the Ottoman Empire under Faisal I bin Al-Hussein bin Ali Al-Hashemi and received commission to form the Northern Army’s military band. On October 3, 1918, Nahmee accompanied Faisal, the Northern Army, and British Imperial troops into Damascus. This was, of course, a part of the campaign that included British military figure and diplomat T.E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia).

By his own account, Nahmee references leaving the Middle East for the United States to join family. A trans-Atlantic vessel named the Roma departed from Marseilles 15 June 1920 and docked in New York 3 July 1920 with Leon S. Nahmee on board. Within a few months, Nahmee settled at 4700 6th Avenue in Brooklyn and submitted his first papers for naturalization by 1921. At his Brooklyn residence, Leon lived with his mother, brother, and sister – Karoline Nahmee (48), William Nahmee (26), and Margaret (20). Karoline and her youngest son William Nahmee immigrated to the United States in 1914. Margaret may have arrived with Leon or shortly after. Leon and Margaret worked as a piano teacher and shop machinist respectively. Karoline worked from home and William, at least in 1925, was unemployed.

|

| First papers for Leon Solomon Nahmee. Courtesy of Ancestry.com |

Nahmee arrived and settled in the United States just as the political tides turned against immigrants. The 1924 Immigration Act or the Johnson-Reed Act limited immigration from Syria to one hundred per year. Determined to continue his career as a musician and composer, Leon Nahmee released his 72-page book of “Oriental Piano Selections” in 1925. In this regard, Nahmee began to rival better-known composer Anis Fuleihan and composer, phonograph label owner, and radio star Alexander Maloof. In addition to music publishing, Nahmee produced and manufactured Nahmee Oriental Airs piano rolls. We do not know for certain how many songs Nahmee released on piano roll; if fact; no known roll seems to exist anywhere in the United States. Several private individuals and collections such as the Washington Street Historical Society and the New York Public Library have copies of Namhee’s book of music. The book's title page gives the business address for Nahmee Music Company as 571 47th Street in Brooklyn, while the Syrian American Press at 104 Greenwich Street printed the publication. Songs included titles like "Bulbul El-Afrah," "Ilay Ha," "Tafta Hindi," and "Al-Labania." Interestingly, Nahmee also reprinted "The Star Spangled-Banner" which had not yet been officially recognized by Congress as the US national anthem. Was Nahmee signaling to someone that he was the type of Middle Easterner willing to assimilate and align with US culture or interests, was this simply a utilitarian action to avoid targeted persecution? Perhaps this suggested some compromise in between? In addition to his book of music, Nahmee arranged the song for and accompanied on piano Rev. Dr. Khalil A. Bishara on this recorded two-part single on Bishara's vanity label.

|

| Dr. Bishara and Leon Nahmee on a personalized Bishara label recorded by the Electric Recording Laboratories. |

|

| Leon S. Nahmee's 1925 "Oriental Piano Selections." Courtesy of the University of Minnesota TC Andersen Library, Immigration History Research Center Archives, Minneapolis, MN. |

Interestingly, many of Nahmee's piano compositions resulted from his listening to Turkish, Syrian, and Egyptian phonograph records. Once in the United States, Nahmee purchased some of his phonograph records from A.J. Macksoud, one of Little Syria's long-time record dealers, importers, and sellers, who had embarked on a venture producing his own record label. Songs by Anis Salloom, Georges Saqqal, Mitri al-Murr, Nadim Nasre, Daoud Housni, Ahmad Shaweesh, Mahmad El-Darwish, Saleh Abdel Hay, Mahmad Ali Lehbi, and Bouna Abdullah made their way into Leon Nahmee's reworked piano arrangements.

Nahmee commenced work on another book of musical compositions and a score for the play “Saul & David,” he also married in 1929. On a mildly cold 12 January 1929, Leon Nahmee left a briefcase filled with music books and the score for “Saul & David” in a taxicab. Out of desperation, Nahmee placed “Lost” ads in several city newspapers offering a cash reward for the return of his case and its contents. Whether he ever retrieved the briefcase remains unclear; Nahmee continued to teach piano from his Brooklyn address and eventually produced “Saul & David” for a performance at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Among those who appeared in the show was aspiring actress and singer Rose Kando Mahkoul. On September 19, 1929, at the Grace Baptist Church on Sixth Avenue & 53rd Street in Brooklyn, Leon Nahmee married divorcee and mother of four, Rose Mahkoul. Interestingly, Rose Kando, the granddaughter of a British Army captain and a Syrian woman, was born in Damascus in 1890, educated in a Lazarite convent, immigrated to the United States around 1909, and married Selim Mahkoul. The couple had Nicholas (1909-1991), Victoria (1911-1991), Edward (1913-1989), and Alexandra Catherine (1919-2005) before they divorced. Records conflict on where the majority of the Mahkoul children were born. The 1920 Census lists as all the children born in New York, but the 1930 Census notes all but Catherine were born in Ohio.

Throughout the 1930s, Rose Mahkoul Nahmee became quite the performing artist, socialite, businesswoman, and public relations representative for Leon Nahmee and her children. Above most things, it seems Rose Mahkoul Nahmee wanted aspired to be an actor and singer. To be sure, Nahmee told the press that her interest in performing arts harkened back to her childhood in Damascus. She habitually broke out into spontaneous song only to be hushed by her parents and relatives because she was a girl. As a child, young Rose sought refuge in her room under the covers where her singing attracted less attention. Immigration to the United States did not change attitudes towards her public performances; also encourage by a priest at Saint Nicholas Cathedral in Brooklyn, elders in the parish even frowned on Rose’s singing religious songs in church. There was not winning with cathedral elders. Strict family members supposedly hindered her from auditioning at the Metropolitan Opera. After meeting Leon S. Nahmee, Rose appeared in “Saul & David” and “The Queen of Sheba” at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Outside these more public performances, Rose busily toiled from home developing her career, promoting her husband’s work, and foregrounding the achievements of her children. For example, in 1933, Rose hosted a New Year’s Day party featuring her husband Leon and daughter Alexandra on piano, Arabic singing by herself, and dancing by Victoria and Alexandra at their home at 4700 6th Avenue in Brooklyn. A few weeks later, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle featured Rose Mahkoul Nahmee in an article about cooking Syrian cuisine. Highlighted were her kibbeh, lubee, and malfouf. Nahmee’s cooking stood among at least six stories about dishes from other nations written by Margaret Mara.

|

| Rose Makhoul Nahmee in one of her performance costumes. The Brooklyn Eagle, 14. December 1932. Courtesy of Newspapers.com |

Both the Saint Nicholas Young Men’s Club and the Lebanon League of Progress threw their financial, organizational, and moral support behind Rose and Leon Nahmee. The Saint Nicholas Young Men’s Group was a social and cultural organization for men formed from members of Saint Nicholas Syrian Orthodox Cathedral in Brooklyn. The group functioned since the 1910s and, of course, Saint Nicholas Cathedral founded in 1895. The Lebanon League of Progress harkens back to 1911 and Naoum Mokarzel established it and became the group’s first president, while working as founding editor of Al-Hoda newspaper. According to historian Stacy Fahrenthold's Between the Ottomans and the Entente:the First World War in the Syrian and Lebanese Diaspora, 1908-1925, the League had chapters throughout the Americas including in the United States, Cuba, Canada, Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil, and maintained a Maronite-leaning, French-mandate-for-Greater Lebanon supporting stance. The League’s original purpose was “to lobby for retention of Mount Lebanon’s administrative privileges in relation to the Ottoman government” and it later proved instrumental in processing passports and other travel and citizenship documents for Syrians in the mahjar and acted as a major recruiter of mahjaris for the Legion d’Orient during World War I. The League’s membership and chapters spread to “four continents.”

The 1920s ushered in the era of the radio and by the 1930s radio threatened both the record industry and the popularity of piano rolls. A number of Arab Americans, Alexander Maloof, Toufic Moubaid, Louise Yazbeck, Anis Fuleihan, Fedora Kurban, and others performed on and conducted orchestras for radio broadcast and by 1933 the first Arab American produced radio music and news program – the Arabian Nights Radio Program on WCNW- appeared. Leon Nahmee worked as a printer, by this time, but according to reports the Nahmee had “just embarked upon making piano-player rolls of Arabic songs” when radio ended any serious prospect for this endeavor. Sadly, the equipment for producing the rolls still stood in 1932. What were Rose and Leon to do with all the Syrian folksongs they had translated painstakingly from Arabic to English?

One of several moments of musical convergence occurred in May 1935 when Saint George’s Syrian Orthodox Church in Paterson, New Jersey, held a musical program following its mass. Saint George’s Orthodox Church traces its roots to 1919, although the church received its official charter in 1921. The event featured Rose Mahkoul Nahmee on vocals, Leon Nahmee on piano, and Petro Trabulsy on violin. Years later, during the course of World War II, Trabulsy put together his Arabian Orchestra, established his own label, and recorded several songs with up-and-coming singer Najeeba Morad. Singles included #1125-1126 “Ya Zalem” and #1127 -#1128 “Fal-yahya Uncle Sam.” On another occasion in 1935, Rose appeared in a solo concert in Pawtucket, Rhode Island hosted by the Damascus Society at Saint Sadie's Church.

|

| In 1935, Leon Nahmee accompanied Petro Trabulsy and Najeeba Morad at a New Jersey concert. Later, Morad performed "Long-Live Uncle Sam" on Trabulsy's label. Courtesy of Richard M. Breaux collection. |

If the Nahmees appeared to be a happy couple to the press and the public things were quite different behind the scenes. Rose filed for a divorce from Leon on the grounds of abandonment on 2 August 1942 and Judge Frank E. Johnson ruled in Rose’s favor on 25 February 1945. Unsatisfied with the decision, once willing to reconcile, and convinced he had only given in to his wife’s demands, Leon appealed the ruling. At the center of the divorce rested the argument that Rose pulled the majority of the wait in supporting the family while Leon moved from job to job or was unemployed. This despite the fact Leon had worked as a printer, piano teacher, song writer, piano tuner, and for the WPA during the latter parts of the Great Depression. After the judge determined there were holes and flat-out exaggerations in Rose’s testimony in the earlier proceeding, the judge ruled on Leon ‘s behalf this time around.

|

| Leon S. Nahmee's World War II draft card. Courtesy of Ancestry.com |

With his divorce from Rose Mahkoul Nahmee officially finalized, Leon Nahmee packed his belongings and moved clear across the United States from Brooklyn to Los Angeles, California. Determined to resume his career as a musician and music teacher, Nahmee announced his arrival in the local Arab American press. He took up residence at 737 Crocker Street, Los Angeles. While Los Angeles had more than its share of amateur musicians, a number of professional Arab American musicians had connections to the film industry in Hollywood and greater L.A. Leon found work as a piano and organ tuner for a number of churches in the city. Within two years, Nahmee moved to 415 W 79th Street. Interestingly, Leon Nahmee refused to declare a political affiliation or party in 1948, but by 1952 he was a member of the Democratic Party. We don’t know much about Leon Nahmee in the years between 1952 and 1956, but on 2 October 1956, Leon S. Nahmee died in Los Angeles. He had no children by birth to claim his estate when a public notice appeared in the Los Angeles newspapers in November 1956.

| The courts initially decided in Rose's favor in the first case. |

Rose Mahkoul Nahmee continued her life as a socialite, of sorts, in Brooklyn’s Little Syria for the next sixteen years. Her parties, dinners, and illnesses received coverage in the Caravan and Brooklyn Eagle. She died 15 December 1972. Edward Mahkoul lived until 1989. Nicholas and Victoria Mahkoul lived until 1991. Alexandra Mahkoul Kretzschmar married Theodore Kretzschmar in 1952 and died 27 May 2005.

Special thanks to:

Michael K., J.G., The University of Minnesota, Immigration History and Research Archive Center, T.C. Andersen Library, Minneapolis, MN.

Richard M. Breaux

© Midwest Mahjar

Comments

Post a Comment